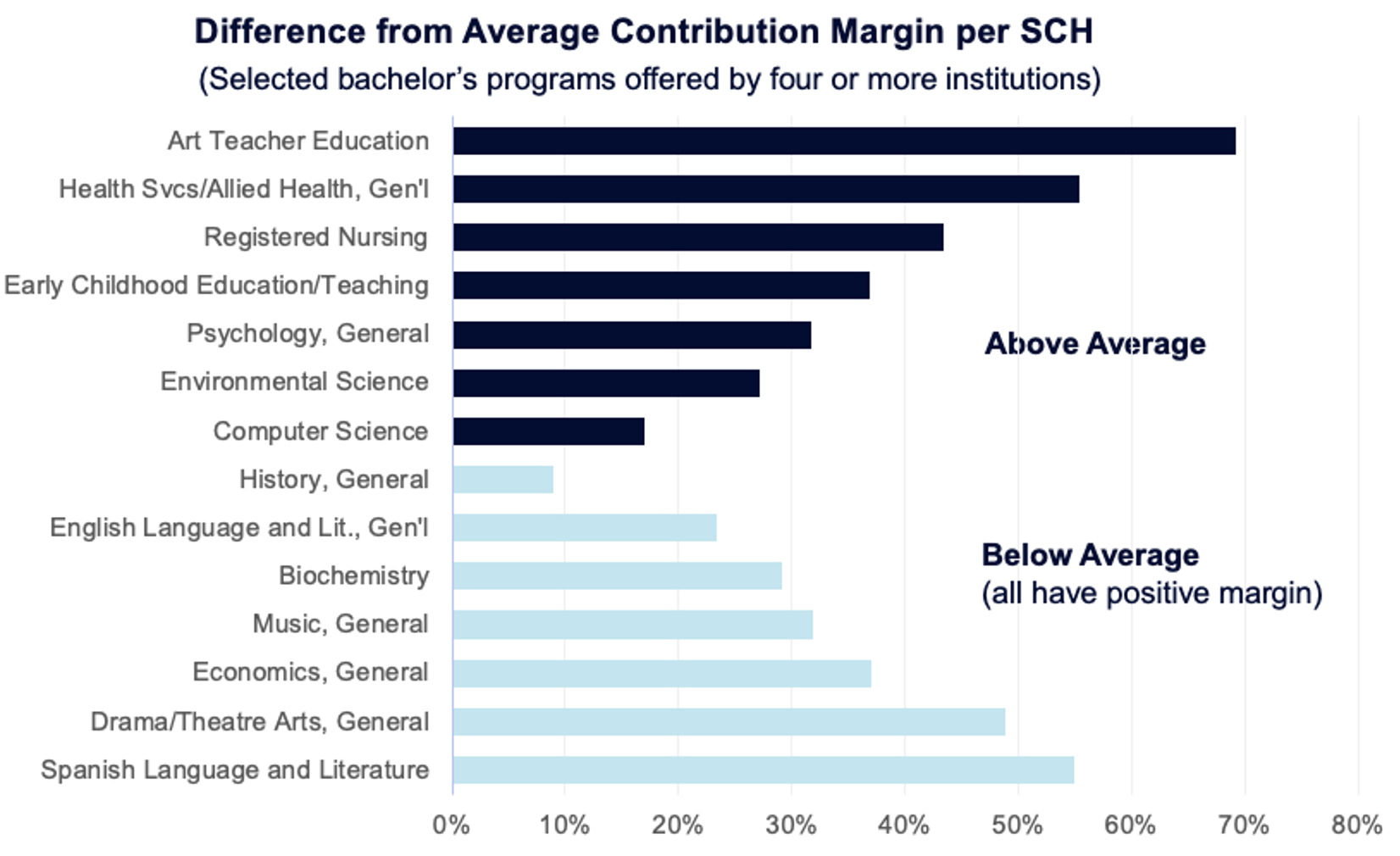

The outcome of program economic analysis is not always intuitive to me. Using our benchmarking data, we calculated the average margin per SCH across over 850 programs at sixteen institutions (see the chart below). You may expect that programs with lower-cost faculty and lots of general education courses, like History and English, would have above-average margins. Both have below-average margins—History is almost 10 percent lower than average, and English trails the average by over 20 percent. Computer Science, which has to compete for professors with highly paid private sector jobs, still manages to produce margins that are more than 10 percent above average. Nursing, which has notoriously high costs and class sizes that are often constrained by accreditors, has margins that are 40 percent above average.

Which Programs Generate Above-Average Margins?

Your program margins are likely to be different from many of our benchmarks. Please don’t guess or use rules of thumb, which are likely to be wrong and are certainly unnecessary. Program economic analysis allows you to know which programs are contributing to your institution’s financial health and which ones need help to survive.

The Variation Concept of Program Economics

Variation is a hallmark of program economics (and curricular efficiency). In a well-run production facility, the cost to produce a part is highly predictable, but the cost may not have been so predictable when the part was first introduced. During the early stages of production, considerable time is spent refining the process, reducing cost, and improving reliability so that the part is consistently the same size, shape, and cost. This level of engineering does not seem present in higher education. As a result, the revenue, cost, and margin for programs and courses are startlingly different. Recently, a client and I reviewed their cost per SCH by course. Their norm was around $300 per SCH. The highest was $2,500 and the lowest was under $100 per SCH—the most expensive course cost 25 times more per SCH than the least expensive. When we filtered to include only courses at the same level (e.g., 400-level courses), the variation remained. As it turned out, at the high end, a full professor was teaching a class with two students, despite an institutional policy that all courses have at least six students.

In manufacturing, a process with a high degree of variation is referred to as out of control: It has not yet been engineered well enough to be predictable. Higher education is intrinsically a complex process; bringing it under “control” is likely to prove difficult, and a high degree of cost control may not even be desirable. In theory, cost controls may stifle the creativity and innovation that is needed for students and institutions to flourish. Perhaps the level of control should vary by type of institution, program, student, and funding— but not by accident. The curriculum for some programs is well-defined, often by programmatic accreditors, and they attract enough students to accurately predict enrollment. The desired outcomes may be defined by formal tests and certifications, such as state bar exams and the NCLEX exam for nursing. In these cases, it would make sense to have predictable processes that produce the target outcomes at lower cost. The same level of predictability may be more difficult to achieve in less defined fields, like history or undergraduate psychology. While the ideal level of process control and predictability may vary, from what we have seen, there is plenty of room for improvement in almost every institution, department, and program.

If the results of margin analysis vary widely and are often counterintuitive, what drives them? Why do they differ from our expectations? For those who are drawn to Zen-like metaphors, a cactus thrives in the desert while a maple tree dies in a drought because it has many more branches and leaves. For a less Zen explanation, the more courses you offer, the more likely that cost per SCH will be high and unpredictable.